A question of facial recognition

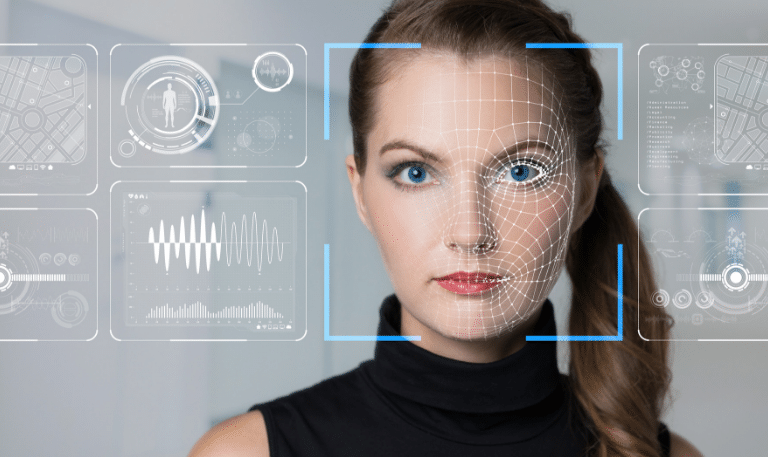

The ethics surrounding the capture and use of facial recognition technology are complex. Who makes the rules that govern biometric technology?

Thanks to advancements in artificial intelligence, the use of facial recognition has spread rapidly over the last few years and shows no signs of slowing.

From unlocking smartphones or streamlining passport queues, to anti-terrorism and crowd surveillance, the use of facial recognition technology is now expanding to improve security and reduce fraud in banks, help diagnose patients with autism, and assist retailers to determine factors such as age, gender and mood that could affect the behaviour of customers in their stores. Indeed, the facial recognition market is predicted to be worth $9.6 billion (US) by 2022.

In Australia, we are already quite familiar with biometric technology speeding up passport control, and we now have the added convenience of being able to use e-gates to enter the United Kingdom. Also in Europe, by 2020 a new Entry/Exit System is set to record biometric data of all Third Country Visitors to the Schengen Area, a move which it is hoped to have a serious impact in the fight against serious crime and terrorism.

Closer to home, other recent developments include a trial of facial recognition technology by a Melbourne university to combat exam fraud and has also been used to help casinos exclude problem gamblers. Soon, it could even replace ATM card pins and magnetic strips, thanks to technology currently being developed by NAB in partnership with Microsoft.

The city of Perth is set to go live with Briefcam facial recognition as part of its $1 million smart cities trial. The cameras installed will be capable of detecting your gender, clothes colour, the speed you are travelling at, and your movements.

However this, along with recent news that the technology has already been deployed widely at sports matches and concerts in Queensland over the last year, has raised questions about the public’s consent and awareness regarding their biometric data being captured in this way.

If we look to China, large-scale surveillance of its citizens has practically become the norm, with around 200 million CCTV cameras keep a watchful eye on the country’s 1.4 billion citizens. Whilst there is no doubt about the positive benefits of increased safety and quality of life through the prevention of violent crime, apprehending identity thieves, and the convenience of paying for the goods and services, these must be weighed against wider implications of such large-scale surveillance becoming the norm.

Many of these issues have been debated in the courts around the world over the last year, with a slew of legal challenges questioning who has the right to the public’s biometric data, how should it be used and whether users have given consent for it to be collected. Google won a lawsuit in December 2018 that claimed it was using facial recognition without users’ consent, similar cases against Facebook and Snapchat are still pending. These are all being prosecuted under the Biometric Information Privacy Act in the US State of Illinois. In the UK, a Cardiff man is suing the South Wales Police for taking his photo and capturing his biometric data without his consent.

Of equal importance are doubts concerning accuracy of the technology and its potential for racial and gender bias, particularly following a recent ACLU test in the US that incorrectly identified members of Congress.

It is against the backdrop of these concerns that San Francisco recently legislated to ban facial recognition technology in the city until these issues have been ironed out. Whilst this step may seem a little too dramatic, there is no doubt that there is a need for deeper investigation into the ethics surrounding the collection and use of biometric data, and its regulation. This need has also been recognised by The UK government, who plan to delve into the ethics of surveillance as part of National Surveillance Camera Day on June 20th 2019.

Amongst the technology giants, opinions are varied, with some clearly seeing the need for further investigation. Microsoft chose to not allow its software to be utilised by law enforcement to scan the faces of all drivers pulled over and Google is waiting for “important technology and policy questions” to be resolved before releasing its own general purpose facial recognition technology. Amazon, on the other hand, is already licensing its Rekognition software to police agencies and federal immigration services.

What is evident is that biometric technology has the potential to make a huge positive impact, making lives more convenient and far safer in a myriad of ways. The Australian Government’s Identity-Matching Services Bill, which promised to allow the use of biometric data to tackle identity fraud, law enforcement, national security, protective security, community safety, road safety and identity verification lapsed with the dissolution of Parliament in April 2019.

This leaves us without firm legislation governing biometric technology, whilst its use continues to grow. Let’s hope that the issues surrounding the use of facial recognition will be adequately considered, allowing the security industry to take advantage of its benefits, whilst still protecting the civil liberties of the public as much as is practical to do so.

The ethics surrounding the capture and use of facial recognition technology are complex. In the absence of clear guidelines from the Australia government, organisations would do well to create their own polices around when and where facial recognition can be used, how long and where the data will be stored, who will have access to it, and how it will ultimately be used.

For more insights and innovation, attend the Security Exhibition & Conference 2019 by registering here.

-

Stay up to date with the latest news and Security updates.

- Subscribe